Robert Sholl is a performer, improviser and writer on twentieth-century music. He is a trained Feldenkrais practitioner and teaches at the Royal Academy of Music, London, and the University of West London.

To listen to music is to listen to the past, present and future of ourselves. We cannot hear music before recordings, but the ways in which it was heard and played is present in what remains in our world: in diaries, letters, treatises, musical instruments, art, clothes, behaviour and reasoning, ethics, buildings and, of course, musical scores. Our human inscape and the seemingly ephemeral and invisible act of listening is therefore omnipresent in the phenomenal world.

| The idea of hearing what cannot be heard has a libidinal charge, as if it is somehow forbidden or even mystical. To lift this veil is one of the tasks of musical composition, performance and research. Musical listening is human, subjective and fallible, searching for a particular perspective (a metaphor that already defers to the visual); and it is intimately connected, in neurological terms, with the other senses. The study of music is a result of these faculties, but, somewhat ironically, it often reveals the gap between music (as sonic text) and the human interaction with this through listening; closing this gap is the task of music study. | |

Music exists in itself as text and in a state of waiting to become a realization. Listening therefore seeks for a future, for what is yet to be heard. To search for this future is to become aware of the nature of our own drives and desires. The invisible attractor, the unknown something that is forever being looked for but that must remain unfound, what in Lacanian thought would be called petit object a, is operative. That we will never reach the ‘Beethoven-ness’ of Beethoven, for example (the study of the composer's music circles around this liminal point), is one primal reason that this music remains so desirable, and why this desire must be fed. This is why it is also an imperative for our species that (this) music be reinterpreted, rerecorded, reheard (from the past) and reimagined.

To listen to our desire might also make us attentive to the aspects of preservation, value, identity, race and genre in our culture. Listening therefore rebounds and renews itself in ever-new ways. It is closely connected to the real presence of the past, and the veneration of culture. This listening provides a form of authentication through and a grounding in a sacral engagement with the past. It is not merely honoring the dead, or keeping a tradition alive as a form of obligation, but a nourishing of our continuing validity in the world. To disavow this listening would leave us as specters living in the half-light of a shadow-world.

Listening, then, is life (the dead do not listen): it is a form of movement and an animation of our inner worlds. By listening, it should already be clear here that I mean a form of multi-sensory awareness, not merely hearing with the ears. The desire to hear and rehear ourselves must be set alongside other aspects of human desires to sense, smell, taste, touch our histories, ourselves and others’ bodies. For musicians, the hands are a primary source of listening. We know that the hands occupy a large portion of the brain’s motor-cortex for good evolutionary reasons – they are useful tools for cleaning, feeding, procreation and the proprioception of the world. The philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy has written about the anxiety to touch, but anyone who observes small children will know of the abandon with which they touch themselves and everything else, how touch is a primal connection to their parents (to the mother in particular). This desire is awakened with consciousness, and it is channeled and tempered (as part of burgeoning human maturity) by the requirements of society. Consciousness becomes awareness through the listening of touch and the touch of listening.

Infants have the untrammelled joy of touching, and this is something that remains with musicians and is discovered afresh. Thinking of one’s instrument or of music is already a form of desire. We know from neuro-physiology that this intention is already a form of thinking in action in the motor-cortex. As pleasure-seeking beings this is unsurprising. We are more likely as a species to use things in our lives that are pleasurable, to be with people who provide pleasure, and to seek out experiences that mark our lives when they are pleasurable. The movement scientist and somatic educator Mosche Feldenkrais defined his ‘Method’ as ‘making the possible impossible, the possible easy, and the easy aesthetically pleasurable’. This is what musicians and creative artists do every day, and this pleasure is fundamental to (musical) learning and to our continued being-in-the-world.

Feldenkrais saw very clearly that there was (and still is) too much learning in our society that is not pleasurable, that is not joyful, and that is driven by will and not skill. He understood that if we could not do primitive movements – such as rolling over, getting out of bed, brushing our teeth, walking and standing up – then we would be in trouble. These problems would find other harvest homes, effecting anxiety, sexual dysfunction and other higher functions such as playing a musical instrument. He also thought that it is in what we do well, or that it is in what we think we do well, that we find our limits and the way these come to define us. Desire to do therefore is not enough; there must be a quality of lightness, ease, pleasure and joy in any thought and action in order to surpass these limits. This quality is transferable. His ‘Method’, known as the ‘Feldenkrais Method’, sought to improve peoples’ self-image – their understanding of themselves in the world – so that, in a utopian vein, they might be able to improve the life of others.

This goal should, I would argue, also form part of listening, but any discussion of the future of listening must also provide some means of (and also reasons why) this function should be improved. If listening is fundamental to the subject, its definition and identity, then to improve this facility is to improve our being-in-the-world. The human nervous system is so subtle that very small variations can make enormous changes in the motor-cortex. But, before imagining some suggestions for methodologies to facilitate such subtle changes in our musical perception, let us imagine an unsubtle social scenario, and one that I think most people have either witnessed or been involved in at some stage in their life, to understand the way in which listening can be inhibited.

In a busy shopping mall, a mother and small child have stopped for a break. The child has seen something they desperately want and subsequently been told they cannot have. The child starts to get agitated and jumps up and down (something that we know from neurological studies of dancers and mirror neurons is one of the movements that most enervates the brain). The parent is increasingly distracted from her welcome cup of coffee and tries to speak to the child. But at this point the child’s motor system is flooded with movement and with emotional agitation – listening becomes almost impossible. You might have noticed this child in yourself when someone was speaking to you and you were thinking of something else. You heard the timbre of their voice possibly, but not the words, nor their sense.

The mind can fold many activities into one; it has been shown that multi-tasking is not possible (people who do so in fact switch their attention quickly from one thing to another). The practice of music requires a form of unitary attentive listening. Fundamental to practice is a continual chain of habit-forming and habit-breaking. The subject becomes what I would like to think of as a malleable fulcrum in time moving towards what the developmental psychologist Esther Thelen has called ‘adaptive flexibility’ – what in musical parlance could be called virtuosity.

Our habits, including our patterns of listening, are formed in gravity, through our proprioception and through our sense of ourselves in the world. Listening, like any other activity, is subject to unconscious (or what Feldenkrais would call ‘parastitic’) habits that we may not be aware of; how we act in any one capacity shows up in others including listening. So, the question of the future of listening then becomes one of becoming aware of our habits, of what we do because of learning, because of instinct and even (perhaps especially) in what we think we do well.

In listening or playing music, we do not suddenly become a different person. Thelen and Linda B. Smith have shown (through an adaptation of Conrad Waddington’s epigenetic landscape) that the groove of our habits becomes deeper in our sensorium over time and through repetition. At first sight this appears obvious, but here are some more acute examples that concern inter-sensorial listening. If we practice a certain passage in a piano piece looking at the left hand, our experience of this moment will be through the left hand. The visual here provides focus for listening that would, following Feldenkrais’s thought, require disruption, the momentary imbalance on the fulcrum, for example, that is caused by looking at the right hand. Practicing with page turns can throw up similar issues – which hand do you use to turn and when? How does this disrupt your playing or hearing of the music: in other words, can you hear the music without the page turn? These examples show that what is needed is an active awareness and an enactivist approach to finding other ways of doing something.

If we think about why we are good at getting two numbers to equal six, this is because we can do this in so many ways (including using different operations and negative numbers). The French pianist Alfred Cortot unwittingly used this Feldenkraisian principle in his éditions du travail where he provided different fingerings for the same passage (for Chopin’s Études for example), but what he was really providing was different ways of listening and thinking through the fingers. Yet if we think that playing an instrument is not merely executed with the fingers but with the whole body, then we must look at the tonus of the muscles in the neck, the tension between the eyes, the space between the teeth, the tonus of the hips, and so on.

Even more specifically, to listen to music is to listen to the quality of another’s nervous system. To listen to Beethoven’s music is to hear not merely what he heard, synthesized and reimagined, it is to hear into a part of himself that only music could reveal even to and for him. Listening therefore can be heard. In listening to and studying Beethoven’s music, it is possible to listen to the history of his listening practices (his habits), his potency, the potential and the malleability of his habits. But it is also to listen to the way, through his practice, he brought a refinement, an intention and a purpose, and economized or folded myriad parasitic possibilities into a unitary ideal (a score).

This is a form of creative listening from the past that we try to make present today. The arrow of time is not reversible, but rather we spiral into it revisiting different points of listening, making intersections with different listening perspectives and making intelligent differentiations and discernments. Feldenkrais believed that one of the qualities of flexible movement was its reversibility. Listening itself cannot be reversed, but we can use listening creatively as a tool to perform reversals. Here is an example of this kind of flexible thinking.

Improvisation is a profoundly creative activity that demonstrates the intersection of past, present and future listening. What seems to happen spontaneously only seems to be that way. It has bubbled up from somewhere, and this is why it is important to practice improvisation and to increase the amount and the quality of ‘petrol in the tank’, to increase the resources of an internal (unheard) listening that connects one’s fingers like a tap to an unknown musical reservoir. It is not a question of manufacturing surprise, but of creating the conditions within oneself that allow one to be surprised. So here is an exercise in reversibility using the beginning of Mozart’s well-known piano sonata in C, K. 545:

Example 1: Mozart, Sonata in C, K. 545/I opening

Firstly, notice if it possible to hear the melody line of the opening without hearing the harmonies underneath (or at least to hear them peripherally – another visual metaphor). Here is the melody and a representation of it as a series of pitches. Could it be transformed and distorted in a different register, slowed down, put into a different key (the minor mode) and made into a funeral march? Or could something more essential be extracted from Mozart’s original, which sounds almost like fairground music in its simplicity. Could it be moved up an octave or more, sped up, and perhaps made to sound like a hurdy-gurdy? It is worth listening in this experiment to a number of things: how does the original maintain its presence in the transformation, at what point does the original disappear, and what does this form of artistic deformation do to the aesthetic meaning of the original?

And now to find a way to reverse this process. Take the funeral march from the ‘Eroica’ Symphony or from Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2, and try to make it into a circus theme, a satanic march or an innocent Mozart-like theme with an Alberti bass. The list of listening possibilities then spirals out from these options. These examples provide instances of neuro-plasticity, and of the subject negotiating various possibilities and using their intelligence to select better listening options. This is a listening practice that can be developed with or away from the instrument.

When you think about this exercise, try to pay attention to what you hear in yourself, your beliefs and what sounds come to your mind. This exercise shows that the future of listening must not be about will, but skill. If, like children, we need to obey the injunctions to ‘pay attention!’ and ‘listen up!’, we also need to listen with more discrimination, more closely and more imaginatively. Here are three suggestions of how we can help ourselves:

We therefore should speak of the risk of listening. To organize the body and mind means to find the most direct and most efficient way of listening, and this requires experimentation. We need to be aware of what else participates in our listening, and the way in which we are already, as the composer John Cage showed, embodied in an ecology of listening in and to the world. This means that listening allows a form of reflexive soma-critique in which questions can be asked of ourselves, our mind/body and of the worldly constructions within which we exist, and that these things return questions to us.

One of the questions that listening returns to us is how to be more comfortable with ourselves. Feldenkrais maintained that most people do not know how to be comfortable, how to perform actions with ease and therefore to derive delight in themselves and others. This is a profoundly important question for musicians. I have spoken of listening as a fulcrum, as a risk and a necessary lack of certainty, but there also needs to be integration of listening, synthesis and understanding. A certain imbalance is essential to learning, to finding other representations and perceptions of the world. How we react and listen to our own disorientation is key.

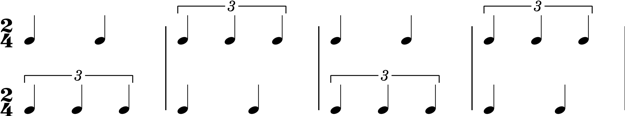

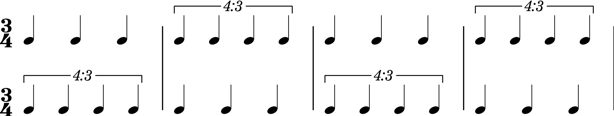

A better quality of listening and integration can be derived from inculcating a sense of physical softness into action. To illustrate this idea, try this exercise. Sit at a table and tap with your fingers on the tabletop (this exercise can also be done in other ways and in other places). Tap three in one hand and two in the other and then immediately reverse this (it becomes more complex if we make it 4:3 and 3:4). Here are both possibilities to try:

Example 2: Two rhythmic exercises

As you do this, first notice to which hand your attention is drawn, and then reverse it. If your right hand is drawn to playing the top line, try to reverse this. Also notice the force you use to tap: could it be lighter? As you do this, let your attention be drawn to the tonus of the eyes, the mouth, the neck, the upper and lower back. Pretty soon, you might realize that this listening exercise involves the whole body (this might be more evident if you filmed yourself doing the exercise). Try doing this exercise slower, make it clearer, easier and lighter, and stop regularly (the brain integrates material in the period of non-doing). This is another exercise of listening and reversal, and how you do it can have an effect on your musical perception. Examining your actions and thinking around this exercise might also reveal something about how you listen to yourself and how kind you are to yourself.

The future of listening is one in which we want to be able to hear more of what is outside and inside ourselves, and to improve the quality and efficiency of listening. Certainly, this can be aided by electronic and prosthetic means (try putting these exercises into a music-printing program to hear how a machine does it). Careful and intelligent listening will also be a necessary part of our survival as a species. This would require listening to the unknown place from which the ‘Other’ addresses us, which in turn necessitates empathy, patience, love and the willingness to be vulnerable. So we need to listen softly, slowly and with kindness for others and ourselves. Listening offers an opportunity to be a better human being and to afford others the same opportunity. There is therefore a delight to be found in listening; it provides for a form of learning that is part of our human endowments and rights.

Associate Professor of Aesthetics at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (MOME) in Budapest, Bálint Veres offers a philosophical account of the theatrical and opera arts, as well as Richard Shusterman's recent conceptualization of art as a form of dramatization.

Sergio Ospina Romero, incoming Assistant Professor at the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University, Bloomington, reflects critically on the principal scholarly narratives about the creation and dissemination of jazz, its U.S. appropriation and its resonance with local Caribbean musical styles.

Contemplating our present-day musical culture of 'post-fidelity', musicologist Mark Katz weighs up what we have lost - and what we might want to regain.

Brown University Professor David Wills journeys from the bells of Edgar Allan Poe, through Mahler's 5th and David Bowie's Hunky Dory, to the rustle of poplars in New Zealand - all while on a train, with no headphones or earbuds.